the Parsonage

the Parsonage

This was the house that brought me to Sedgwick. I loved everything about it — the ramshackle steps leading up to it, the torn-off shutters, the way it was situated on a little rise above the water.

In fact, I had built a whole fantasy world around this house based on the few pictures of it posted on the Internet. I imagined fashioning a small caretaker’s apartment out of a falling down ell at the back and living there in the summer while I rented out the house to amiable summer tourists for whom I would leave baskets of salad ingredients that I grew in my own vegetable garden. In the autumn, I’d walk my dogs through the streets of Blue Hill, stopping for coffee and gossip at the Coop and the bookstore. You know, stuff like that. I even changed real estate agencies to get my hands on the inspection report. I knew the place needed work and that I would probably not purchase it, but I was tired of not following through on things I wanted. What if I was missing out on the perfect thing?

My enthusiasm proved short-lived. Despite its splendid facade, the Parsonage had been ravaged over time by the poverty of the twentieth-century Baptist ministers who lived there. They fought back against the home’s decline in ways that seemed downright spiteful. Someone had installed a mid-century bathroom with flamingo pink fixtures on the second floor, and the original kitchen fireplace had been removed, leaving an awkward space between the hall and dining room. But even these faux pas were nothing compared to the most horrible transgression — someone had torn out the main chimneys, leaving only holes in the attic where they had once stood.

I suppose this might seem a bit hypocritical, coming from someone whose last post was about tearing down a chimney stack. But a Federal home is supposed to look like this —

http://www.flickr.com/photos/nhoulihan/3796718332/in/photolist-6Mvb5U-pjfyrZ-gYxqT-xTLfiB-a58jVT-6TqQio-oXnnTV-pHTCVK-qgGu89-598ay3-6zA88t-6zA7Qx-6CpXZk-gvyXKJ-oENpeP-6yLtJs-bRJ8mB-pU5SB5-hg7shq-nMhSfE-6D6SrG-o7NZVi-o5Wds9-7eQZd1-oFcyyV-fqiMk-dWPBPf-i6tnjY-d6oyzU-bCPoUA-oWCnVr-2UfKV-6mQjvS-bRJ7mF-pcJ3mn-o5MRRX-d6tD4S-e4vmva-4CqSyF-4Cve5J-bCPpBU-4CqSTg-72h9L8-7fzsHp-dZtwmE-qY96dw-6jsHu9-uwoZPV-4Cry2R-4CvQLb“House on Greeley Road, N. Yarmouth,” In Awe of God’s Creation

— and I could not get the lack of chimneys out of my mind even as I walked through rooms with far more immediate problems: crumbling plaster, soft floors, and collapsing windows. The youthful contractor who’d been invited by the representing agent turned out to be the perfect antidote to my idealistic reveries.

“I’d just gut renovate the whole thing and put up drywall. And you really don’t want to keep painting the outside. You’ll want to put siding.”

A representative from the Sedgwick-Brooklin Historical Society had come along to meet yours truly, complete with his own agenda. For him the Parsonage was the means to an end, a plain girl he was willing to court as a way to stay close to her beautiful sister. In the tactful, almost regretful way of any hopeless suitor, he wanted to see if I might be able to help. He walked through the rooms with me, listening to my restoration schemes with a preoccupied air. I had the feeling that he didn’t have much faith in the Parsonage. Or at least, he

Finally, he told me there was something else he’d like for me to see.

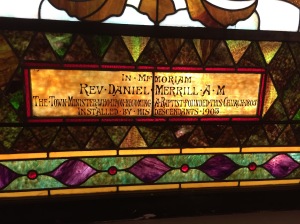

This Greek Revival church is his baby, a high maintenance broad with a penchant for self-destruction. As I tried unsuccessfully to find a good angle from which to snap a photo, he was hurrying me toward the entrance so that he could show her off. We paused on the portico, beneath a row of peeling Doric columns formed from concave pieces of wood that were jointed together and painted to look like marble — just long enough for me to note the placard above a central stained glass window, commemorating the date.

The church was built in the early days of the village as a triumph over those parsimonious “sprinklers,” the Congregationalists. Minister Daniel Merrill, who founded the Congregationalist church in Sedgwick in 1794, underwent a righteous conversion to Baptistry just ten years later, taking the majority of his parishioners with him. After Merrill’s death, they hired a prominent Bangor architect named Benjamin S. Deane to build the church, which was completed in 1837.

Like several of Deane’s other buildings, the church is listed on the National Registry. It is a perfect gem of a building; some consider it one of the finest examples of Greek Revival architecture in the state of Maine. It is also a mess. Early attempts to correct the foundation have led to misalignment in the structure of the building higher up. No one has been able to stop leaks in the belfry, and the interior smells powerfully of mildew.

The real surprise was waiting for me inside: seven glorious stained glass windows, each one donated by a wealthy parishioner at the turn of the last century to commemorate the centennial of the church. An expert confirmed that they are the work of neither Tiffany nor LaFarge — the windows have been attributed to both — but whoever made them had considerable talent; they are some of the most beautiful stained glass windows I’ve seen in an American church. Although stained glass is appropriate to a Revival building, there is something incongruous and oddly secular about the rich and flowery windows. It adds a touch of eccentricity.

While I walked around examining the windows and other, more homely details of the interior, I heard the story of the Historical Society’s many efforts to restore the church. There had been errors in judgment and experts who proved unworthy of the challenge. Even if the society sold the Parsonage for the full asking price, it would be a drop in the bucket; the cost of having just one window professionally restored would be something like $100,000. It’s fair to say he went on at great length. I don’t mean this unkindly. The Blue Hill Peninsula is a place where people come to wage war with historic properties, and regaling others with tales from the battlefield is a hard-won privilege. I sensed a weariness, perhaps a shade of bitterness, and as I embark on my own war with time and architecture, I can definitely see why.

It’s hard to love a building when she doesn’t love you back.

Community efforts to restore the First Baptist Church of Sedgwick are ongoing. Please read this 2010 article in Bangor Daily News to learn more, or contact the historical society directly if you are interested in helping.

Sedgwick-Brooklin Historical Society

P.O. Box 171 Sedgwick, Maine 04676

207.359.8086